Meet Pamela

Pamela started painting as a ten-year-old, when her mom enrolled her in an adult art class. Her dad taught her how to draw on paper napkins after dinner. Decades later, her artwork expanded from individual paintings to include participatory art with a focus on healing and resilience. Drawing on Pamela’s own journey towards restoration, following the breakdown of her parent’s marriage during her childhood, these responsive projects help foster community through art, creativity, and storytelling.

After raising four children, Pamela reached one of her life goals and completed her master of fine arts degree from Azusa Pacific University, forty years after her undergraduate work. Overflowing with creativity, innovation, and passion, Pamela hopes to complete another twenty years of work before retiring.

Pamela Alderman Art

In 2006, Pamela launched her art business out of her garage studio. After several years of hard lessons and failure, Pamela closed her online store with art prints and art cards. She pivoted to accepting a limited amount of commission work each year and creating interactive community-based work. With this change, Pamela Alderman Art took off. Year after year, while exhibiting her work at ArtPrize, a large art event held in Grand Rapids, Michigan, her audience kept growing. People felt drawn to her hands-on projects.

Her first interactive public installation, called Braving the Wind, focused on cancer survivors. For the project, she prepared 1,500 interactive note cards for audience members to write notes. Those supplies lasted for three days. Over the next two weeks, her husband and mom scrambled to buy more note cards. By the end of the event, 20,000 individuals had written note cards to remember their loved ones battling cancer.

A couple years later, more than 20,000 people wrote wishes and prayers for children in need at Wing and a Prayer. Each year her interactive installations, based on sex-trafficking, bullying, or letting go, continued to expand with 50,000, then 65,000, then 70,000 participants. But Pamela openly shares the secret behind her work at her public speaking events: “My prayer team and I circle the location for my next art project every month for a year leading up to the following exhibit. My business model isn’t complicated. Every year I follow the same steps of prayer, hard work, and integrity. God continues to grant success and the audience continues to grow.”

“It’s been a huge honor showing my work in Phoenix during the 2015 Super Bowl and at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.,” says Pamela. “But I’m just as content creating a unique fine art piece with a few incarcerated teens from Girls Court or the profoundly handicapped children at Pine Grove Learning Center. Whether my audience is 70,000 people or seven individuals, I put the same intense effort into each art piece. I love to be around other people, and I love to create art. With a combination of the two, I love my work!” For her next goal, Pamela hopes to write a book about her healing art journey.

Healing in Arts

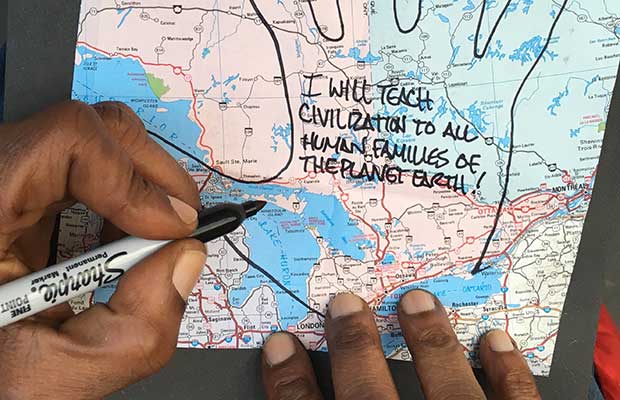

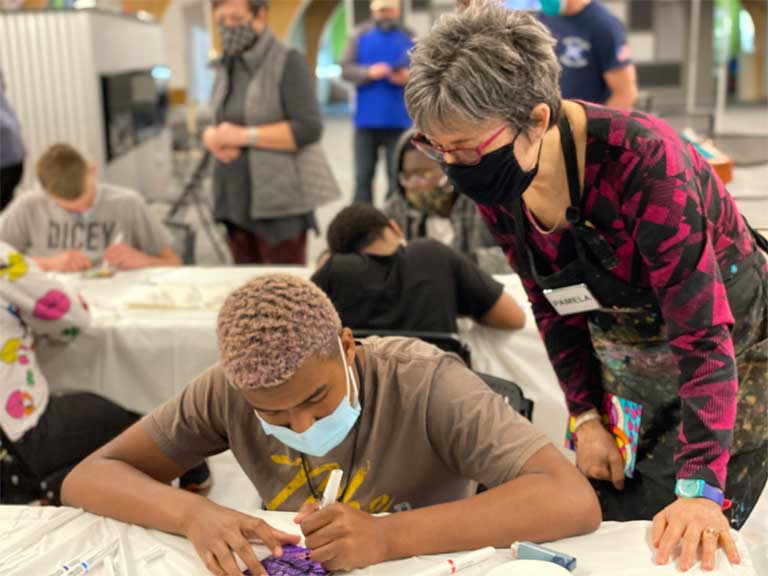

In 2016, ten years after starting her art business, Pamela’s mentor urged her to start a nonprofit. For the first several years, a local business man, Marvin Veltkamp, generously hosted what Pamela calls, “Healing in Arts,” under Libertas Foundation. Last fall, seven years later, Healing in Arts became an official 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Pamela describes it, “Along with my creative team, I create interactive collaborative art projects.” This work fosters creative care and resilience with community groups, including cancer patients, Congolese refugees, children on the autism spectrum, sex trafficking survivors, and veterans struggling with PTSD.

These various interactive projects cultivate a sense of community by demonstrating the value of each and every person. Participants respond to the transformative power within these hands-on projects while exploring relevant topics and how to be part of the solution. Pamela says, “Because of our donor support, many experience release and gain a sense of new beginnings in our collective journey towards growth. Amazingly, my childhood trauma ended up fueling this volunteer creative work years later.” Art serves as the catalyst for personal and corporate healing.

It is Pamela’s dream to put another fifteen years of sweat equity into Healing in Arts before handing it off to younger women of color. Currently, Healing in Arts board members form a diverse creative group that crosses boundary lines of skin color and generations and locations with a single mission of empowering people and inspiring hope through collaborative art.

If you would like to be part of something bigger than yourself, click here and help spread healing through art.

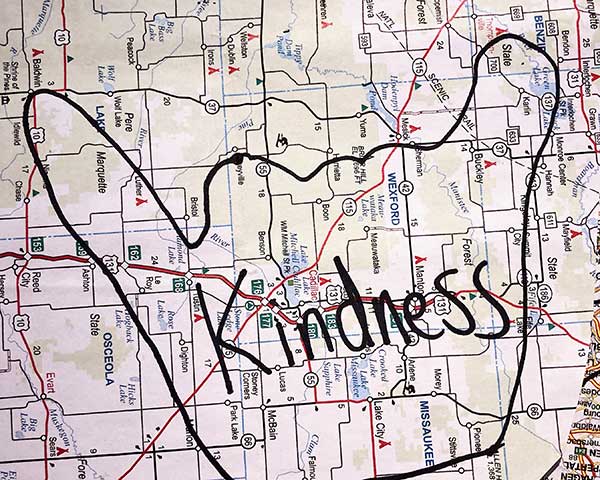

The butterfly effect, an alternative scientific theory, challenges us to consider that every tiny action could have a large effect. The smallest deed or word–positive or negative–has the potential to change the course of an individual’s life. Whitney’s story demonstrates how to turn heartache into an opportunity for hope:

The butterfly effect, an alternative scientific theory, challenges us to consider that every tiny action could have a large effect. The smallest deed or word–positive or negative–has the potential to change the course of an individual’s life. Whitney’s story demonstrates how to turn heartache into an opportunity for hope:

Twenty years ago, the Columbine High School tragedy happened. America sat in shock, frozen before the television. Kids were gunned down. At school. The killers laughing. Like playing Fortnite. In real life.

Twenty years ago, the Columbine High School tragedy happened. America sat in shock, frozen before the television. Kids were gunned down. At school. The killers laughing. Like playing Fortnite. In real life.